Leadership in China is shaped by thousands of years of philosophy, decades of political transformation, and the realities of managing growth in one of the world’s most complex economies. It is not a carbon copy of Western frameworks. Instead, it blends hierarchical values, moral responsibility, and group-centered decision-making into a distinct model that continues to evolve.

Understanding how leaders operate in China is critical for those navigating international business. Whether working with a local partner, managing a cross-border team, or analyzing competition, the success of any engagement depends on grasping how decisions are made, how power is exercised, and why trust often matters more than contracts.

This article breaks down the most common leadership styles in China, their cultural foundations, how they differ from Western models, and how they change in response to global influence and generational shifts.

Historical and Cultural Influences on Chinese Leadership

Photo from unlimphotos.

Modern Chinese leadership styles are not improvisational. They are structured by centuries of philosophical discipline and institutional frameworks that continue to shape how authority is earned, exercised, and sustained. These styles are not arbitrary—they reflect deep beliefs about order, duty, and power that differ fundamentally from many Western paradigms.

Confucianism: Hierarchy as Moral Responsibility in Chinese Leadership Styles

Confucianism has long defined the ethical architecture of leadership in China. Unlike transactional or performance-based models standard in Western organizations, Confucian leadership is based on a moral contract. A leader is not simply an executive; they are expected to embody personal virtue (ren), proper behavior (li), and loyalty to social order. Their authority comes from serving as a moral reference point, not from formal designation alone.

This creates a leadership model that reinforces vertical relationships, but not through coercion. Like a father in a family, the leader commands respect by demonstrating self-discipline, emotional restraint, and benevolence. Subordinates are expected to obey, not out of fear or obligation to a process, but from recognizing the leader’s ethical standing. Decisions are made with this moral framework, which often favors long-term relationship preservation over short-term gains or operational efficiency.

Confucianism also introduces the concept of face, preserving dignity in interpersonal interactions. Leaders are careful not to humiliate subordinates publicly, and performance feedback is often wrapped in indirect language to protect social harmony. In return, subordinates rarely challenge authority openly, reinforcing stability in decision-making and communication.

Collectivism: The Leader as a Steward of the Group in Chinese Leadership

While Confucianism defines the ethical ideal, collectivism governs the leader’s functional role. Chinese leaders are expected to manage for the benefit of the group, not the individual. The organization is viewed as an extended family, and the leader must ensure cohesion, prevent internal conflict, and safeguard the group’s reputation.

This approach informs how Chinese managers allocate responsibility, reward loyalty, and resolve disputes. Consensus-building often happens behind closed doors, and decisions, though issued from the top, are usually preceded by informal alignment within trusted circles. Leaders avoid visible confrontation and depend heavily on internal social contracts, especially Guanxi (关系), the system of relational obligations that determines influence and trust within the group.

The prioritization of group welfare also means that employee performance is not evaluated solely on merit. A worker who maintains team harmony may be more valuable than one who excels independently but disrupts cohesion. This is especially true in state-owned and family-run businesses, where interpersonal loyalty can outweigh individual metrics.

Legalism and Bureaucratic Centralism in Leadership Styles

While Confucianism idealizes virtuous leadership, Legalism provides the operational logic for command and control. Emerging during the same historical period, Legalism advocates for strict rules, centralized authority, and a top-down enforcement structure—attributes that continue to influence how Chinese institutions are run, especially in state-influenced sectors.

Leaders shaped by Legalist thinking emphasize procedural control, performance discipline, and strict adherence to hierarchy. Organizational success is seen as the product of clarity and order, not creativity or debate. This often results in performance regimes that reward obedience and penalize dissent, with minimal tolerance for ambiguity in decision chains.

Today, the legacy of Legalism is visible in how Chinese firms structure power around a central leader and enforce policy compliance through clear channels. The influence is decisive in government agencies and large-scale enterprises where rules, rather than discretion, protect internal order and external accountability.

Post-1949 Communist Doctrine: Loyalty, Sacrifice, and Ideological Unity

More recent ideological layers also shape contemporary Chinese leadership. After 1949, the Communist Party institutionalized new expectations of leadership based on political loyalty, personal sacrifice, and ideological alignment. The leader’s role extended beyond business performance to include moral-political guidance.

This influence remains in play today, especially in organizations with close ties to the state. Leaders are expected to uphold “party-building” initiatives, promote social stability, and demonstrate alignment with national priorities. Loyalty is internal and upward to superiors, government authorities, and, in some cases, to broader ideological goals. Even in the private sector, politically sensitive industries often require executives to navigate parallel managerial and political accountability layers.

Unlike the Confucian hierarchy grounded in moral legitimacy, Communist-era leadership frameworks introduced legitimacy based on revolutionary struggle, policy alignment, and institutional service. That mindset still echoes in how some business leaders, particularly older generations, frame their role as protectors of the collective, willing to endure personal hardship to sustain the organization.

Cultural Continuity in a Modern Economy

While globalization, digitization, and market reforms have diversified management practices, the cultural expectations surrounding leadership have not disappeared. They have adapted.

In today’s China, it is common to find executives trained at global business schools who still uphold Confucian paternalism in motivating teams, apply Legalist structure in delegating control, and practice collectivist loyalty in promoting internal talent.

Chinese leadership today is not a rejection of tradition—it is an evolution shaped by the need to compete globally without discarding the frameworks that have long defined how trust, duty, and stability are achieved.

Common Chinese Leadership Styles in China and Approaches

Photo from unlimphotos.

Authoritarian (Autocratic)

Traditional Chinese leadership is often top-down. Decisions are made by senior leaders or managers and rarely questioned by subordinates, reflecting high respect for authority. This is especially evident in government agencies and legacy state-owned enterprises. Research confirms Chinese executives tend to be “naturally authoritarian and… tend to focus on results”.

Under this style sets goals are set unilaterally, and employees are expected to follow instructions. High power distance means many workers expect clear directives and assume subordinates will obey without debate.

Paternalistic: A Key Trait in Chinese Leadership Styles

The most distinctive Chinese style combines strong authority with personal care. Paternalistic leaders see themselves as parental figures. They command obedience and care for employees’ welfare.

For example, Huawei’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, exemplified this blend of hard and soft leadership. Ren integrated strict military-style discipline (clear goals, sacrifice, obedience) with a doctrine of “taking care of the troops” – rewarding staff with high pay and support.

In other words, he demanded loyalty and performance yet cultivated a familial culture. This resonates with traditional expectations: Chinese workers often expect leaders to act like “paternal figures,” providing direction and personal support. Under a strong leader, the result is an environment of loyalty and cohesion, although it can sometimes stifle criticism or initiative from lower ranks.

Consultative (Participative)

Modern Chinese firms, especially in the private and tech sectors, increasingly blend traditional authority with consultation. Consultative leaders seek input from their teams and value teamwork.

As China opened up and young managers were exposed to Western practices, some managers moved “from being initiative-driven to encompassing more comprehensive management styles” that balance goals with employee well-being.

For example, many joint ventures and innovative companies now solicit employee feedback on essential projects. While ultimate decisions remain with the boss, leaders may hold meetings or seek advice before committing.

This consultative tone is a recent adaptation: though still framed within hierarchy, it reflects a shift toward engaging workers’ insights and addressing their needs, without fully relinquishing authority.

Photo from unlimphotos.

Transformational Leadership: The Future of Leadership Styles in China

This style—where leaders inspire change, articulate a bold vision, and empower followers—has historically been more Western, but it is gaining traction in China’s fast-moving industries. Tech entrepreneurs and newer executives often act as visionary change agents.

For instance, Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma, became known for his charismatic, mission-driven leadership. He broke from strict autocracy and instead emphasized common goals and humility. Analyzing his approach, researchers note that “abandoning the autocratic management style” in favor of open dialogue and shared vision boosted employee loyalty and reduced turnover.

Similarly, Chinese studies suggest that when elements of transformational leadership (like inspiring vision and encouraging innovation) are adapted to fit China’s collectivist context, they can strengthen team unity and spark creativity. In practice, transformational Chinese leaders preach company missions, encourage employees to exceed expectations, and celebrate innovation – all within a framework that respects hierarchy and harmony.

Transactional

Like everywhere else, transactional leadership – setting clear tasks, using rewards and penalties, and focusing on efficiency – is common in China. It particularly suits bureaucratic environments and routine businesses.

Leaders in many state-owned enterprises and manufacturing firms rely on performance metrics and standardized procedures. Employees know exactly what is expected: meeting targets earns bonuses, missing them may mean censure.

This approach aligns well with China’s emphasis on order and discipline. (As one review puts it, transactional leadership creates a “structured environment where employees clearly understand expectations and the consequences of meeting or failing them.” In China, this often shows up in systems like multi-tiered performance appraisals and bonus structures that reinforce hierarchical accountability.

Leadership Styles in China: Case Studies in Major Companies

Huawei (Ren Zhengfei)

Photo from Huawei

The founding CEO of Huawei, Ren Zhengfei, is often cited as a case of strong Chinese-style leadership. Ren’s approach has been described as paternalistic and authoritarian. Using his military background, Ren built Huawei’s culture around clear goal-setting, strict discipline, sacrifice, and absolute obedience.

He enforced high performance standards and unwavering loyalty – yet, in keeping with paternalism, he also aimed to “take care of the troops” by rewarding top performers with generous compensation. Under Ren, Huawei grew rapidly into a global telecommunications leader. However, his hard-driving style has been criticized recently for causing employee burnout and requiring adaptation as Huawei confronts changing markets.

Overall, Ren exemplified a leader who combined iron discipline with a deep commitment to his employees’ welfare, consistent with Chinese expectations of a paternal figure.

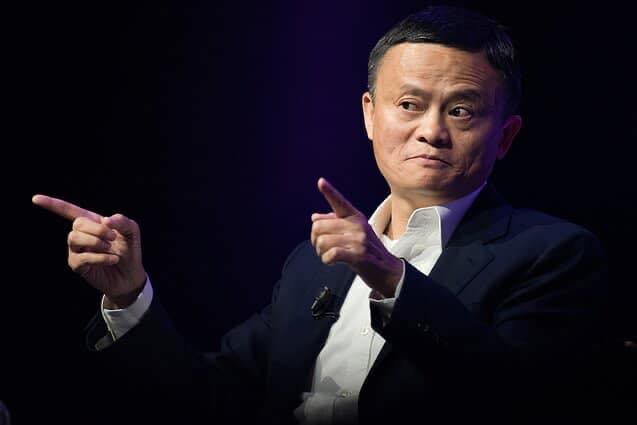

Alibaba (Jack Ma)

Photo from Jack Ma’s official Facebook account

In contrast, under founder Jack Ma, Alibaba showcases a more visionary and people-oriented style. Jack Ma broke with the model of the aloof boss. He is known for his charismatic motivational speeches and encouraging staff entrepreneurship.

One observer notes that Ma consciously “abandoned the autocratic management style that he grew up with in China” and welcomed diverse opinions and feedback. He famously said 30% of people will never believe you, so don’t expect everyone to follow blindly – instead, “let them work for a common goal.”

By splitting large units into smaller teams, he kept the organization agile and emphasized that success came from collective effort, not the leader’s ego. Surveys indicate that Jack Ma’s humility and inclusive leadership engendered great employee loyalty, leading to low turnover.

In summary, Jack Ma’s leadership blended traditional Chinese values (loyalty, unity) with a Western-inspired focus on vision and empowerment, reflecting a transformational style adapted to Chinese culture.

ByteDance (Zhang Yiming)

Photo from the Facebook handle of Zhang Yiming

ByteDance, the parent of TikTok, provides an example of technology-driven, innovative leadership. Founder Zhang Yiming, an engineer by training, emphasized continuous innovation and data-driven strategy.

In the early startup phase, Zhang showed hands-on problem-solving and strategic foresight, creating a company culture that encouraged experimentation and risk-taking. He focused on recruiting top tech talent and fostering loyalty by allowing staff to pursue creative ideas. Zhang’s leadership style is marked by a “relentless pursuit of innovation,” particularly in artificial intelligence and machine learning, and a long-term vision rather than short-term gains.

Unlike a stereotypical authoritarian boss, he promoted adaptability. As one analysis notes, ByteDance’s culture under Zhang prioritized innovation and employee initiative. This approach has paid off, and ByteDance’s apps have seen explosive global growth (TikTok ranked in the top 5 apps in 82 countries). In essence, Zhang combined Chinese collectivist values (team loyalty) with Silicon Valley-style agility and innovation in leadership.

How Globalization Is Reshaping Chinese Leadership Styles

Global trends are influencing Chinese leadership in several ways:

Returnee (海归) Leaders and Their Impact on Leadership Styles in China

Photo from unlimphotos

China’s rapid globalization has prompted a wave of “sea turtles” – professionals who studied or worked abroad and have returned. Most senior Chinese executives overseas would consider returning, and about two million have done so in the past few years. These returnees bring foreign training and management habits back to Chinese companies. They often serve as bridges between Western best practices and Chinese cultural norms.

For example, leaders who spent years in Europe or North America may introduce more consultative or analytical decision-making into their teams while operating within China’s hierarchical context.

At the same time, these executives understand China’s nuances – they “know the complexities of the Chinese market” and can navigate guanxi and global corporate governance. The influx of returnees is helping Chinese firms build more globalized corporate cultures, balancing local traditions with international standards.

Rise of Gen Z and New Workforce Norms

China’s workforce is becoming younger. Gen Z workers (those born after 2000) have different expectations from older generations. Surveys and cultural trends (such as the “lying flat” or tang ping movement) indicate that many young Chinese employees resist 12-hour days and strict seniority. They value work-life balance, creativity, and personal growth.

One human-resources analyst notes that China’s new generation is “widely regarded as individualistic, selfish and creative” – quite different from their parents’ generation. This generational shift is forcing leaders to adapt.

Companies are experimenting with flatter structures, more flexible policies, and perks to retain young talent. A manager who demands blind obedience may find younger employees disengaged; instead, modern Chinese leaders are learning to motivate through purpose and respect for employees’ needs.

Digital and Tech Leadership

The explosion of China’s tech sector has created a breed of digitally savvy leaders. Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance, and other internet giants’ founders and executives often come from engineering or entrepreneurial backgrounds and run companies with agile, data-driven mindsets.

These leaders prioritize innovation cycles, rapid decision-making through algorithms, and the empowerment of tech teams. They are comfortable with remote and flat team models (when feasible) and often engage younger employees via open communication channels. The success of apps like TikTok—the #1 downloaded app in 82 countries and counting—shows how these leaders leverage China’s IT strengths.

Digital transformation initiatives in government and industry mean even traditional leaders must be tech-aware. For example, many Chinese officials now emphasize “digital governance” and introduce metrics dashboards; similarly, managers in all sectors must guide their organizations through the AI and e-commerce revolutions.

In short, globalization and technology are pushing Chinese leaders to be more innovative, data-informed, and global in outlook, even as they remain rooted in China’s cultural context.

The Role of Keynote Speeches in Leadership Development

Keynote speeches have become essential for building modern leadership credibility in China’s business world, and no one exemplifies this better than Ashley Dudarenok.

Photo by Ashley Dudarenok

As a globally recognized China digital expert and keynote speaker, Ashley brings deep insights into leadership, digital transformation, and consumer behavior. Her speeches at international summits, including TEDx, G20, and Harvard events, have helped shape how global audiences understand China’s evolving business leadership.

Ashley Dudarenok: Bridging Cultures Through Thought Leadership

Ashley founded ChoZan and Alarice, two firms focused on Chinese consumer trends and digital marketing. Through her speeches and books, she decodes how Chinese executives lead with a mix of authority, speed, and cultural sensitivity.

Her leadership frameworks emphasize:

- Emotional intelligence in cross-cultural management

- Female empowerment and inclusive leadership in Asia

- The strategic use of digital storytelling in Chinese leadership

She speaks to Chinese and global leaders, advising companies on how to lead teams across borders while navigating the nuances of Guanxi, face, collectivism, and data-driven execution.

Why Ashley’s Keynotes Matter in China’s Business Climate

Ashley models a new style in a country where leadership has long been expressed quietly: public, data-backed, and inclusive. She elevates leadership conversations from tactical execution to strategic vision and cultural fluency. Her work is particularly relevant in China, where digital expansion demands leaders who can communicate across platforms, generations, and geographies.

For aspiring Chinese and foreign leaders alike, Ashley Dudarenok’s speeches offer a masterclass in leading confidently while remaining grounded in the cultural dynamics defining success in China.

Book Ashley Dudarenok to inspire your leadership team with actionable insights and global relevance.

What Foreign Managers Should Know about China Leadership Styles in China

Photo from unlimphotos.

For non-Chinese managers operating in China, cultural fluency is crucial. Experts emphasize the following tips and best practices:

Respect “Face” and Hierarchy

Always be mindful of miànzi. In China, personal dignity and social standing are paramount. As one leadership guide warns, Chinese employees “go to great lengths either to save face or to save someone else’s face,” because a person “would rather die than lose face”. Foreign managers should never publicly embarrass or sharply criticize an employee. Corrections are best given privately and with tact. Acknowledging seniority and titles in introductions also helps.

Build Guanxi (Relationships)

Relationships underpin business in China. Develop trust through small gestures—meals, gifts (if appropriate), and consistent follow-up on commitments. Keep in mind Guanxi’s emphasis on reciprocity and obligation. For example, spend time nurturing the personal relationship before asking for a favor. Demonstrating trustworthiness is often a prerequisite to employee loyalty.

Communicate Indirectly and Silently

Avoid bluntness. Chinese teams often use indirect language or pause (silence) to consider an idea. Westerners may misinterpret silence as agreement, but Chinese colleagues might simply be reflecting to maintain harmony. If you need clarity, ask questions gently rather than demanding answers. It can engage employees one-on-one rather than in a public forum. Remember that speaking out too boldly can be seen as “showing off,” which may make others uncomfortable.

Encourage Harmony and Collective Goals

Frame tasks as part of a bigger team effort. Emphasize how project success benefits the group and aligns with company values or national pride. In practice, this means soliciting input collaboratively and crediting the team.

One Ashridge consultant advises Western leaders to align their style with local norms: effective expats “adapt to local norms” instead of imposing their home-country approach. This might involve, for instance, celebrating group milestones rather than only individual wins, and showing personal care for team members like a considerate mentor.

Adopt a Paternalistic Touch

In China, leaders who show genuine concern for employees often gain loyalty. Acts of concern—such as checking on employees’ well-being, offering mentorship or career guidance, and sharing in life celebrations—can resonate powerfully.

Chinese business culture notes the notion that leaders “act as paternal figures.” Even foreign managers can practice a mild version of this by taking an interest in their staff’s personal growth and being available as supportive advisors while still maintaining professional boundaries.

Be Patient with Decision Processes

Appreciate that decisions may take time. Involve relevant stakeholders and avoid pushing for rash conclusions. If a Chinese partner hesitates, realize it may reflect a desire to ensure no one loses face or that all interests are balanced. Patience and iteration will often yield better long-term buy-in.

Overall, foreign managers should cultivate cultural intelligence. A successful leader in China learns to navigate social norms (face, gift-giving, respect for seniority) and incorporates them into leadership methods. When foreigners adapt by respecting Chinese values rather than clashing with them, they build trust and effectiveness in their teams.

FAQs About Leadership Styles in China

-

What leadership styles does Ashley Dudarenok emphasize in her consumer and organizational transformation talks?

Ashley highlights customer-centric styles like servant and democratic leadership to help teams align with evolving consumer behaviors. Her sessions guide corporate leaders on fostering inclusive cultures and adapting decision-making frameworks to match modern expectations in China and global markets.

-

How do Ashley Dudarenok’s keynotes help leaders adapt to China’s evolving tech and retail sectors?

Ashley’s keynotes deliver actionable strategies for refining leadership styles using AI, XR, and omnichannel tools. Using case studies like ByteDance and DeepSeek, she shows how situational and transformational leadership models drive innovation and agility in China’s fast-paced tech and retail environments.

-

What challenges do foreign managers face when leading Chinese teams?

Foreign managers may encounter challenges such as navigating indirect communication, understanding the importance of guanxi, and adapting to hierarchical structures. Success often requires cultural sensitivity, patience, and building strong personal relationships.

-

How are female leaders influencing leadership styles in China’s tech sector?

Female entrepreneurs in China’s tech industry are challenging traditional gender roles, bringing inclusive and collaborative leadership styles. Companies like Alibaba and Tencent have implemented policies supporting women’s advancement, reflecting a gradual shift towards gender-balanced leadership.

-

How do Confucianism and Legalism coexist in modern Chinese leadership?

Confucianism promotes moral virtue and hierarchical harmony, while Legalism emphasizes strict laws and centralized control. Modern Chinese leadership often blends these philosophies, advocating ethical conduct within a structured, rule-based system

-

In what ways is the paternalistic leadership model evolving in modern Chinese companies?

While traditional paternalistic leadership combines authority with care, modern Chinese companies question its effectiveness. Research indicates a shift towards more participative and flexible leadership styles, especially in younger, innovative firms

-

How do Chinese leadership styles adapt in cross-cultural collaborations, especially with Western partners?

Chinese leaders often adjust their styles to accommodate Western partners. They adopt more direct communication and participative decision-making while valuing hierarchy and harmony. This adaptability facilitates smoother cross-cultural collaborations

-

What role does ‘guanxi’ play in leadership effectiveness in China?

‘Guanxi’ refers to personal networks and relationships. Effective leaders leverage guanxi to build trust, facilitate business dealings, and navigate bureaucratic systems. It’s a cornerstone of Chinese business culture, often superseding formal contracts.

-

How does the concept of ‘face’ (miànzi) impact leadership and feedback in China?

‘Face’ pertains to one’s social standing and dignity. Leaders avoid direct criticism to prevent someone from’ losing face.’ Feedback is often delivered indirectly, emphasizing the importance of maintaining harmony and respect within the team.

-

In what ways does Ashley Dudarenok’s leadership style embody both Eastern and Western philosophies?

Ashley combines Eastern values such as collectivism and harmony with Western innovation and individual empowerment principles. Her leadership approach encourages collaborative decision-making and respects hierarchical structures while promoting creativity and proactive problem-solving